The Mesmerizing Chronicle of Two Cousins Who Teamed Up to Forge a Legendary Color kingdom

The simple coloring kit they created that dominated the children's art and supply market for the past 122 years

It was considered a technical marvel of its time, featuring an iron hull, a gross tonnage of 4,535, and dimensions of 422 feet in length, 42.2 feet in width, and 34.5 feet in depth.

The SS Bothnia was a British steam passenger ship powered by a 600-horsepower, two-cylinder compound steam engine, built by J & G Thomson, with cylinders measuring 60 and 104 inches in diameter and a 54-inch stroke, operating at 65 psi.

The ship was rigged with three masts, providing auxiliary sail power—a common feature for steamships of the era as a backup for engine failure. It could carry up to 1,400 passengers: 300 in first class and 1,100 in third class (steerage).

Construction on the ship began in the early 1800’s and was completed by March 4, 1874. Its maiden voyage to the U.S. took place on August 8, 1874.

Passengers eager to buy a ticket paid about £5–£7 (roughly $25–$35 at the time, or $700–$1,000 in today’s dollars). If you could afford a first class ticket, you’d pay about $125 to $150 dollars at the time. However if we adjust that amount for inflation in 2025, this would be around $3,500 to $4,200 in today’s dollars.

And the journey itself was quite the adventure, especially if you were departing from London, England.

In fact that was the starting point for C. Harold Smith’s travel to the U.S. He was born in London, England in1860. There’s not much genealogy recorded for his family other than his father was Joseph B. Smith.

Harold’s journey would first be by train or horse-drawn carriage to a major port like Liverpool or Southampton, the primary departure points for transatlantic voyages.

At the time Liverpool was the dominant hub, handling most British emigration to the U.S. The train ride from London to Liverpool, about 200 miles, would have taken around 5–7 hours, costing a few shillings for a third-class ticket.

Once he arrived at the port, Harold would have boarded the ship and then headed to the lower decks where steerage passengers were housed. Passengers brought their own bedding and utensils, and the food supplied was basic—think hard biscuits, gruel, salted meat, and potatoes, often served in communal tin bowls.

The air was stale, reeking of unwashed bodies, seasickness, and coal smoke from the engines. Sanitation was poor, with limited access to toilets (often just buckets) and no bathing facilities. Disease, like smallpox or typhus, was a constant risk.

After departing Liverpool, the ship set sail west across the North Atlantic, on a 3,000-mile journey to New York. The route often skirted the southern tip of Ireland, then headed into open ocean, sometimes passing near Newfoundland before reaching the U.S. coast.

Harold spent about 14 days on the ship until it reached its final destination — the port of New York.

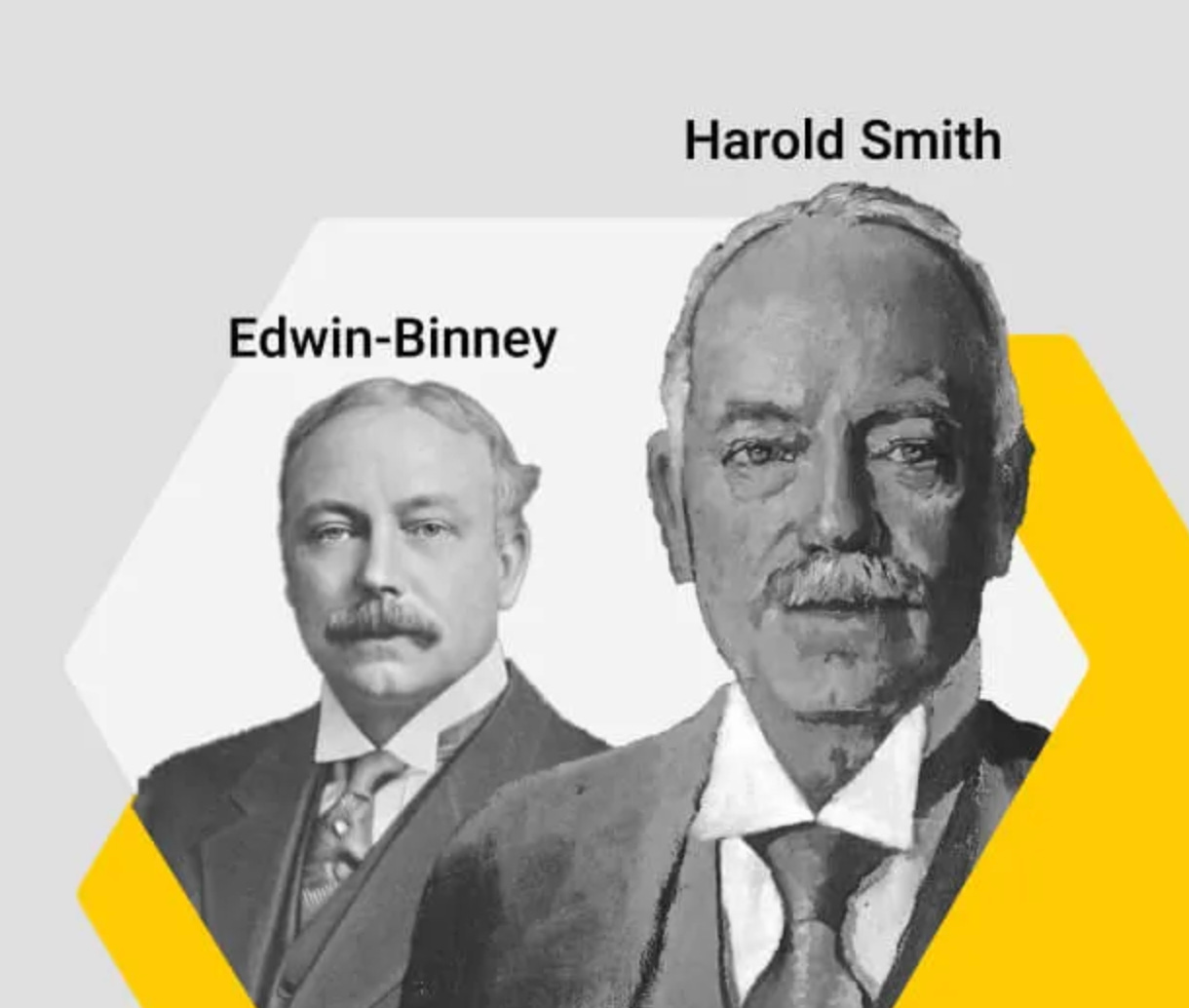

Harold was traveling to New York to meet up with relatives that had already immigrated to the U.S. … his uncle Joseph Binney and cousin Edwin Binney. The two cousins hit it off rather well. In fact the two partnered up to take over an existing business. And let me tell you they didn’t just do a good job they created a lasting legacy in the children’s art supply industry.

And it’s one that has dominated the market for the past 122 years, surpassing all other brands. It all started in the little town of Peekskill, New York.

From Trading Outpost to Trading Center

In the beginning there wasn’t much to Peekskill, which is approximately 40 miles north of New York City. By road, the driving distance is about 41–45 miles, depending on the route, typically via US-9 or the Taconic State Parkway.

By train, the Metro-North Hudson Line covers roughly 41 miles from Peekskill to Grand Central Terminal, with a travel time of about 60–70 minutes.

The town got its name from a Dutch immigrant, Jan Peeck. Originally born in the Netherlands, in 1650 Jan crossed the ocean on a steamship headed towards New York (back then it was known as New Amsterdam).

Jan along with his wife Marie du Trieux opened up a tavern, which served as their main source of income. The tavern, located on Maiden Lane quickly became notorious for rowdy behavior, including drinking clubs, dancing, and serving alcohol on Sundays during church services.

That kind of activity was frowned up back then and just two years after opening their tavern, in 1652 their license was revoked. This was financially devastating for Jan and his wife and their young family of four children, which sometime later turned into ten.

To supplement their income, the couple began trading with local Native American tribes, particularly the Kitchawank. In fact Jan set up a fur trading post near Annsville Creek, where it meets the Hudson River. The creek, initially called “Peeck’s Kill” (Dutch for “Peek’s stream”), gave rise to the name of Peekskill village.

His trading activities with the Kitchawank tribe were among the earliest recorded European-Native interactions in the area, formalized later in the Ryck’s Patent Deed of 1684.

Since Jan spoke both English and Dutch, he acted as a broker between Dutch and English merchants. In 1656, he was appointed an official broker, earning 1.5% per transaction. He also served as an official translator and was part of the Burgher Corps, a citizen militia protecting Fort Amsterdam, appearing on a 1,653 muster roll of 220 names.

He also contributed to building a wooden barrier across Manhattan, later known as Wall Street. There’s a marker in present day Peekskill that commemorates Jan’s arrival, noting his fur trading and contributions as a militiaman and translator.

The little town of Peekskill grew into a prominent hub of activity (mostly mills) because of its location being such a short distance from New York City and located near the Hudson River.

In fact by the late 18th century, Peekskill Landing was a busy port, shipping agricultural goods from Westchester to New York City. Even President-elect Abraham Lincoln made a stop in 1861 at Peekskill’s train station, recognizing the town’s importance as a connecting point for all kinds of businesses, large and small.

The Little Business That Could

One of those little businesses located in Peekskill was the Peekskill Chemical Works founded in 1864 by Joseph Walker Binney.

Joseph was originally born in London England and seeking more opportunity and a better life journeyed to the U.S. in 1860. Four years after his arrival, Joseph established his chemical company in a former tobacco factory near Annsville Creek, in an area later dubbed "Lampblack Hill" due to the soot produced.

At the time he also married Annie Eliza Conklin, and together they had a son Edwin Binney, born in 1866. As soon as he was old enough, which was sometime around the time he turned 14, Edwin joined his father’s business.

Joseph’s company was strategically located near raw material sources, such as McCoy’s rendering works and a tannery, which supplied animal fat and bone for production.

Binney’s initial focus was grinding and packaging hardwood charcoal, a key fuel source, and producing lampblack, a black pigment derived from burning oil, fat, or resin. The lampblack they produced was sold to local foundries and cast-iron stove manufacturers who then used it on the products they sold to customers.

Like many business owners, Joseph faced challenges. For example, in 1870 his factory caught on fire and was burnt to the ground. But Joseph had the resources and determination to rebuild, which he did. The factory reopened a short time later.

But our guy Joseph was a keen business man and realized he should diversify to avoid any other setbacks, particularly fires. So he dabbled in real estate and also worked as an insurance agent for Guardian Mutual Life Insurance, covering Westchester, Putnam, and Rockland counties.

All of his businesses were doing well. And thus in 1880, Joseph opened a New York City office to further expand his chemical business, hiring his nephew, C. Harold Smith to work as a salesman along side his son Edwin.

You Can Say It’s All About the Colors

Harold and Edwin were tasked with helping to expand Joseph’s chemical business. And one way they achieved this goal was focusing on the creation of carbon black — a fine, black powder composed primarily of elemental carbon.

Carbon black was used in inks, paints, and coatings due to its deep black color and durability. Binney and Smith sold carbon black to the printing industry, which at the time was fairly abundant in New York City.

In fact carbon black became the cornerstone of Harold and Edwin’s success. So much so that in 1885, Joseph retired from the company, leaving the two cousins to run the operation. Harold at age 25 and Edwin at age 19 were now head of the company.

The two formed a partnership and renamed the Peekskill Chemical Works as Binney & Smith. As partners, Edwin focused on product development and operations, while Harold handled sales and international expansion.

Edwin was so good at his job that he patented an apparatus for mass-producing carbon black in 1892, which coincidentally earned him recognition from the National Inventors Hall of Fame but not until 2011.

The two also focused on manufacturing more red oxide pigment, which was the primary color used on barns. This gave them a big advantage in the agricultural industry. In addition to the red oxide pigment, they also expanded into shoe polish, securing a niche in the retail industry.

They even created a product called “Staonal” for “stay-on-all,” which was a wax-like marker made with black carbon and used to label shipping crates.

Their focus on colors and new niches had a huge impact on the company’s growth. By the early 1900’s Binney & Smith was well-known as a major manufacturer of pigments and inventions. In fact Edwin experimented with slate waste, cement, and talc, inventing the first dustless white chalk in 1902, which won a gold medal at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

Another one of their accomplishments was the purchase of a water-powered stone mill in Easton, Pennsylvania, which allowed them to mass produce slate pencils for schools.

You see at the time paper was scarce and children used slate boards for writing assignments. And the tool needed to write on those boards were slate pencils.

Their purchase of the mill gave them another new niche to focus on — the education market. And it was a big market for them. For example, by 1900, there were approximately 250,000 public schools in the U.S., mostly one-room schoolhouses, plus private and parochial schools.

All Colors For All the Kids

Now there’s a few ways one can stay in touch with clients … writing to them, phone calls or visiting them directly. And that’s what Binney & Smith did … they sent salesmen to schools to get a sense of what other resources were needed.

One of the items reported back to them by their salesmen was the need for some kind of colored pencil or marking device. Edwin’s wife, Alice who was a former school teacher and worked at Binney & Smith agreed that colored marking tools would serve children well.

So Edwin had his team of engineers reformulate Staonal into something that was safe for children. They replaced the carbon black (a highly toxic material) with non-toxic pigments and used softer paraffin wax.

In 1903, they launched the first box of eight colored wax-like makers, which sold for a nickel and came in black, brown, blue, red, purple, orange, yellow, and green. Of course they needed a name for these new coloring instruments and that they left for Alice.

She aimed for a name that was catchy, memorable, and appealing to children and educators. So she combined the French word "craie," meaning "chalk" and “ola" from "oleaginous,"a term meaning "oily" or "waxy," which described the paraffin wax base.

The two words combined equal Crayola. The name was perfect. It was short, pronounceable, and unique. Then she simply added crayon, which was already a familiar term for a drawing tool made of colored wax or chalk.

The name itself contributed to the product’s immediate success. The 1903 launch laid the foundation for Binney & Smith’s dominance not only in the art supply market but also in children’s education.

Binney and Smith quickly expanded the business. In 1904 they increased the number of different colors from eight to sixteen with larger boxes included. By the 1920s–1930s, Crayola Crayons were distributed across the U.S. and began entering international markets, particularly in Canada and Europe.

Beyond schools, Crayola Crayons became widely available in retail stores, such as department stores and five-and-dime shops, further solidifying them as a household name. By the 1950s, Crayola Crayons was a cultural staple, used in homes, schools, and even art therapy.

Over the next few decades, the company continued to expand the color palette, reaching 64 colors by 1958.

A Multi-Colored Dynasty

Binney & Smith became a publicly held company in 1961, raising capital to fund further expansion and innovation. This marked a shift from a family-run business to a corporate entity.

In 1984, Hallmark Cards acquired Binney & Smith for $204 million, recognizing Crayola’s brand value. This provided resources for global marketing, new product lines, and technological advancements.

By the 1990s, Crayola was sold in over 80 countries, with manufacturing facilities in Easton, Pennsylvania, and later in Mexico and Asia to meet global demand. The company produced 3 billion crayons annually by the late 20th century.

By 1996, Crayola had produced over 100 billion crayons, achieving 99% U.S. household recognition. Marketing campaigns, like the 1993 “Name the New Colors” contest, engaged consumers and reinforced brand loyalty.

In 2007, the company rebranded as Crayola LLC, reflecting the dominance of the Crayola brand over its industrial roots. By this time, Crayola was the world’s leading crayon manufacturer, with over 50% of the U.S. market.

In 2013, the largest box of Crayola Crayons ever created was the Crayola Ultimate Crayon Collection, which contained 152 crayons. The set includes 120 standard colors, 16 glitter crayons, and 16 metallic crayons, housed in a multi-tiered plastic case with a carrying handle and a removable crayon sharpener.

Today Crayola LLC generates over $650 million in annual sales. Its estimated that the company produces nearly 3 billion crayons each year. This is equivalent to about 12 million crayons per day. That’s a lot of coloring!

C. Harold Smith and Edwin Binney’s vision transformed Binney & Smith into a global leader, leaving an enduring legacy in art, education, and culture.

Amazing Quotes by Amazing People

“Artists are just children who refuse to put their crayons down.” - Al Hirschfeld

Easton, PA and the Crayola factory are only about 20 minutes north of me. I loved your story!