Jaw dropping true tale of a retired navy veteran who secretly turned forgotten scraps of food from a tattered trash can into the country's most dazzling snack sensation

Told no by his business colleagues, he went onto create one of America's most well-liked, well-loved, and well-enjoyed tastiest chips with a market value of $3.7 billion

Commissioned on June 9, 1944, the USS Holt (DE-706) measured 306 feet in length, displaced 1,400 tons, and was powered by two General Electric turbo-electric engines, giving it a top speed of about 24 knots.

Its armament included three 3-inch/50 caliber guns, one twin 40mm anti-aircraft gun, eight 20mm cannons, depth charges, and a triple torpedo tube mount, manned by a crew of approximately 186 officers and enlisted personnel.

The ship was used during War World II in some of the toughest battles taking place in the Pacific Theater. In fact it arrived at Hollandia (now Jayapura), New Guinea, on October 25, 1944, just as General Douglas MacArthur’s forces were reclaiming the Philippines.

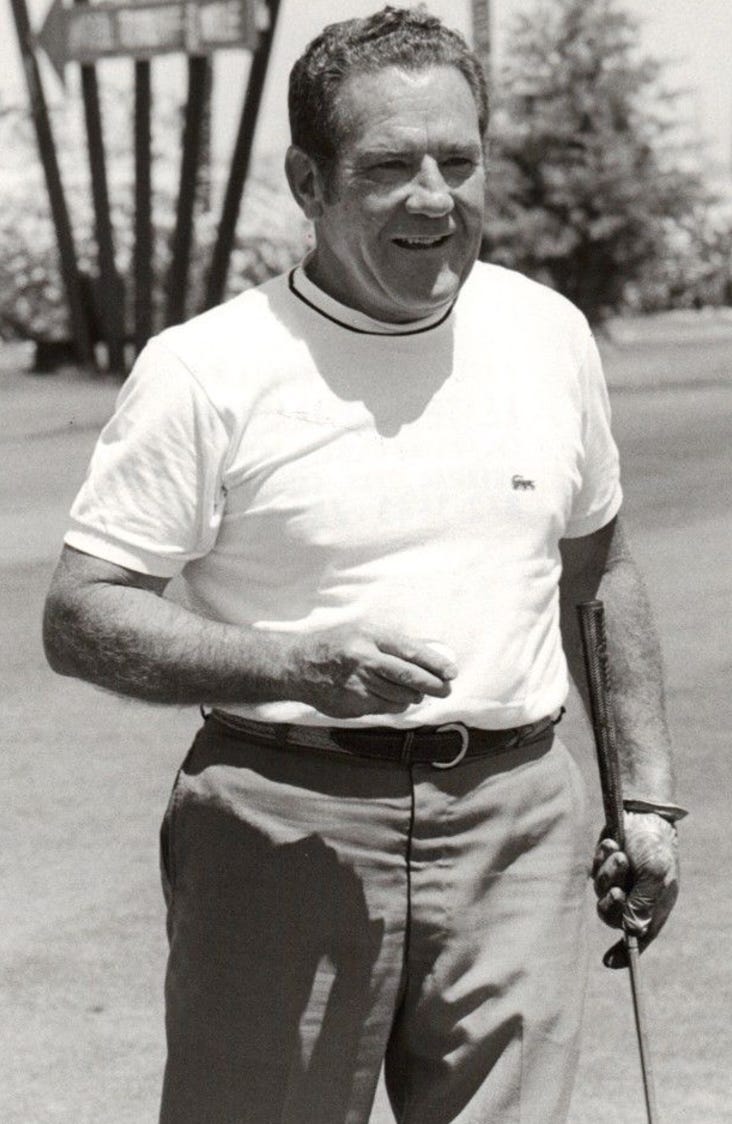

Now one of the crewmen on board was a man named Archibald West, born on September 8, 1914, in Indianapolis, Indiana, to Scottish immigrant parents, James and Jessie West. Sadly, just three years after he was born, Arch’s father died of peritonitis in 1917.

That created a hardship for the family. Arch’s mother struggled to make enough money to care for Arch and his brother Jack. So she sent them to be raised in an Indiana Masonic Home. The boarding home followed traditional Masonic values of charity, community, and moral upbringing.

The home was established 1916 by the Grand Lodge of Indiana to care for widows, orphans, and elderly members of the Masonic fraternity and their families who faced financial hardship.

It sat on over 200 acres, offering ample outdoor space for recreation, work, and reflection, surrounded by the rural landscape of Johnson County, about 20 miles south of Indianapolis.

Arch and Jack most likely lived in a dormitory-style setting, while sharing a room with basic furnishings—bed, desk, and perhaps a small personal space for their ow belongings.

Education was the cornerstone of the boarding home. Arch and Jack either attended school on site or were sent to the nearby Franklin Community School. Either way, they were taught a basic curriculum of reading, writing, arithmetic, and history, often infused with moral lessons.

Both the boys were required to participate in physical activities such as baseball or basketball, or music. And they also had to help around the home, including cleaning the building and taking care of the grounds.

For some children this could be a difficult life. But Arch thrived in this kind of environment. So much so that he earned a scholarship to Franklin College in Indiana, where he graduated with a business degree in 1936.

An Ad Man With a Heart of Jell-O

After his tour of duty was completed and he was discharged from the Navy, Arch traveled to New York. And that’s where he landed a job working as a traveling salesman for Standard Brands. Standard was an American packaged food company originally founded by the J.P. Morgan company.

It quickly merged with some already established manufacturers such as the Fleischmann Company (known for yeast), Royal Baking Powder Company, E.W. Gillett Company (a Canadian baking goods firm famous for Magic Baking Powder), Widlar Food Products Company, and Chase & Sanborn Coffee Company.

By 1940, Standard Brands had climbed to the number-two spot among U.S. packaged goods companies, trailing only General Foods. Its success continued, and by 1955, it ranked 75th on the Fortune 500 list.

One of the brands the company managed was Jell-O. And the man that oversaw that account was none other than Arch West. One of the more popular campaigns that Arch worked on was the obsession Americans had for molded salads. Housewives were encouraged to create their own molded jell-o salad as a centerpiece for the night’s dinner menu.

Other ads included animals like bunnies or peacocks with the slogan, “When I’m eating Jell-O, I wish I were ….”

Jell-O’s jingles also became a memorable part of its 1950s marketing campaigns. One popular jingle, "It’s never too late to make dessert," promoted Jell-O instant pudding as a quick, family-friendly treat.

Working for Standard Brands, Arch had built a name for himself in the industry. And while that in itself might being satisfying for lots of people, it wasn’t quite enough for Arch.

He was looking for a new challenge. A role that offered him much more creative freedom. He wasn’t sure where he’d go and in some ways he left his future up to chance.

His chance came when he took a job working for company selling snack foods.

Pawn A Ring, Make Some Chips

Charles Doolin was about to loose his family’s ice cream business. He had very little money left and was desperate for new ideas.

You see the ice cream sold at the family’s Highland Park Confectionary in San Antonio just wasn’t as creamy at it had been and that’s because the two companies who made it, Mistletoe Ice Cream and Dairyland, were engaging in a price war.

So Charles either had to pay the higher price or use lesser quality ice cream. Neither choice was good for his business. Paying the higher price meant he had to raise prices on ice cream and risk losing customers. And using lower quality cream also meant losing customers.

He was stuck in a “no-win” situation. So Charles was on the hunt for a new treat altogether. On July 10, 1932 he spotted an ad that was placed in the San Antonio Express newspaper. The ad, placed by Gustavo Olguin, listed for sale an original recipe for fried corn chips along with an adapted potato ricer and nineteen retail accounts. The price for all of this … just $100 dollars.

Charles was so intrigued that he wanted to taste the chips. So he drove to the nearby gas station where Gustavo had set up a little booth and was selling his chips to those passing by.

Charles took one bite and thought the chips were delicious. But he also wondered why Gustavo wanted to sell something that was so good. Gustavo explained that he wanted to return to his native home of Mexico and teach soccer.

Charles was ready to buy the business but there was just one problem - he didn’t have the money. But loving Moms always do right by their children and his mother Daisy Dean Doolin pawned her wedding ring to help raise the funds.

She got a whopping $80 for her band.

The remaining $20 … Gustavo said “pay me later.”

With the help of his mother, father and brother Earl the entire family got together in his mom’s kitchen and started making the chips following Gustavo’s recipe. They used Gustavo’s adapted potato ricer and premade masa (corn dough) that they bought in bulk from a tortilla factory across town. Then the four thinned the masa and extruded it through slots cut in the bottom plate of the ricer.

After that part was complete, they snipped the ribbons of masa straight into boiling oil. Gustavo didn’t have a name for his chips, but Charles thought they needed one. After the family tossed a few names around, they settled on Fritos and chartered the Frito Lay Company in September of 1932.

To say the chips were a success is an understatement. In fact by 1947 the company had five manufacturing plants, including offices and a plant on the West Coast, and franchises all around the country. They even set up a restaurant at Disney Land in California called, Casa de Fritos.

While Charles Doolin had a keen eye for business he also had a reputation for fairness and generosity toward his employees. He considered— and called— them collectively the “Frito Family. ” He even sold them discounted company shares, gave them sizable pensions, and often personally presented them with rewards for excellence or years of service. One of those exceptional employees presented with awards was none other than Arch West.

Eat Those Chips in the Trash Can

See as Arch was searching for new opportunity, he found it working at the Frito Lay Company. He used his previous experience of advertising, marketing and selling to help Frito Lay expand their business. In fact he was Vice President of marketing for the company.

But it can’t be all market, market, market and no play. So in the early part of 1960, Arch took his family on a week long vacation to Disney Land. On their way, Arch stopped a roadside stand where a man was selling tortillas.

And that’s where something kind of magical happened … he noticed that the cook would throw small scraps of unused tortillas in the nearby tattered trash can.

The first thought that came to Arch’s mind is there’s gotta be something more the cook could do with the scraps instead of tossing them out. And the thing he thought to do was ask the cook to fry them up. And while you do that, please add some spices to make them taste good.

Now instead of getting rid of the left over tortillas, the chef fried them, added a couple of spices and started serving them to customers. People loved them. I mean really loved them.

When Arch returned to Frito Lay headquarters, he pitched the management team on selling the chips as part of the Frito Lay brand. But they weren’t quite as impressed with the chips and told Arch, “Americans don’t want to eat fried tortilla chips.”

So his fried tortilla snack was rejected. But Arch knew differently. After all, he saw first hand how customers enjoyed the chips. And Dear Reader he wasn’t going to take this NO lightly.

In fact using his own money, Arch secretly developed the fried tortilla snack concept at an off-site facility. He refined the recipe, shaping the chips into triangles for easier eating and adding seasonings inspired by Mexican flavors. He wanted the chips to taste similar to a taco.

Once he had perfected this new chip, he took it back to Frito Lay executives, finally convincing them of the product’s potential after market research he had done showed consumer interest.

They agreed to give the product a test run. But of course, they’d need to give the chips a name. Arch was already a few steps ahead. He simply blended the Spanish “doradito” (little golden thing) with a nod to “Fritos,” prefixed with a “D” for flair.

Now the crunchy, flavorful snack Dorito was ready for the public. The chips first launched in San Diego in 1964. They were a big hit. The company then launched the chips nationwide in 1966. And every year after that, the chips were a consumer favorite.

Arch West’s sharp eyed-chip vision transformed Doritos into Frito-Lay’s second-best-selling product (behind Lay’s), with global sales eventually reaching billions annually.

Today Doritos consistently holds the top position in the tortilla/tostada chip category in the U.S., with a significant market share. Last year sales reached $3.7 billion with over 1.14 billion chips sold.

Arch died on September 20, 2011, at age 97 in Dallas, from complications of vascular surgery and peritonitis—the same condition that took his father. At his funeral, his family honored his legacy by sprinkling plain Doritos over his urn, a fitting tribute to the man who turned a roadside snack into a cultural icon.

As for Charles Doolin, he died of a heart attack on July 22, 1959 in a hospital in Dallas. He didn’t get to experience the success Arch created with Doritos. However the company he created, now owned by PepsiCo is still a strong hold in the industry. Today it generates over $91 billion in annual revenues.

I don’t buy Doritos in my home because I’ll consume way too many. However if there is a bowl full at a party, I’m the first to admit I’ll eat them all in one sitting. Luckily, I don’t attend that many parties.

Amazing Quotes by Amazing People

"A winner is a dreamer who never gives up. Vision without action is merely a dream, but vision with action can change the world." — Nelson Mandela

Great read, Sandy. Your headline drew me in instantly. Who would’ve guessed these humble beginnings of everyone’s favourite snack Doritos? I love knowing this. Makes me want to tear into a bag. But I’m like you and have to avoid initiating contact!